Nine Reciprocities expands what’s possible on an existing dense urban block when architecture is generated within a constructed story of the social, communal, financial, material, and biological context. It is not a solution; rather, it is a means of exploring a new, more circumspect role for architecture and architects, which reiterates the profession’s commitment to craft and careful consideration of space, while adding a new dimension of material stewardship — all in service of an existing community’s needs and directions.

Read the essay

Nine Reciprocities

Over the past century, New York City’s buildings have weathered summers and winters, hurricane floods, and blazing heat — as well as protests, recessions, depressions, and ticker tape. They also hold in their bricks and timbers the embodied human and environmental energy of their extraction, fabrication, and construction. As architect Carl Elefante quips, “the greenest building is the one that’s already built.” And where there are already buildings, there are already people. Does the city need “master” builders and planners, or restorers and adapters?

The architect is just one actor in the physical and social lifecycles of buildings, where “design” is never a one-way directive. Architects are meant to listen, and to build buildings that are good listeners too. How can architectural practice help keep communities intact in the face of climate change and rising inequality? Nine Reciprocities is a 100-year vision for a self-sustaining block in New York City. Through vertical adaptive reuse of existing buildings, we imagine a series of spatial, material, financial, and social platforms for expanding existing communal life. We looked at nine different ways that architecture can serve existing forms of mutual aid and collectivity over this time span: Assembly, Daycare, Gym, Workshop, Store, Office, Greenhouse, Bank, and the Skin.

Our speculations are focused on Manhattan’s Community District Three (CD-3), an area that includes the Lower East Side, Two Bridges, and Chinatown. Each of these neighborhoods faces distinct socio-economic and socio-political challenges; the threat of displacement and exclusion looms equally over all of them. Worrying signs that CD-3 may be transitioning to an exclusionary neighborhood, where low-income tenants are unable to afford rent, are already becoming visible: One Manhattan Square tower demolished a Pathmark grocery store frequented by the middle-income residents of Two Bridges, in addition to obstructing views of the East River and Brooklyn waterfront. Despite ongoing opposition to One Manhattan Square, four more towers are still planned within the same block, while neighborhood groups such as The Coalition to Protect Chinatown and the Lower East Side organize actions against landlords and developers. Analysis from the Urban Displacement Project suggests CD-3 is one of the last areas of Manhattan to fully gentrify. Their data show that large parts of the district are at risk of, or undergoing, gentrification, while remaining areas are deemed “exclusionary” for low-income residents. For these reasons, we thought a representative block in CD-3 would be a useful site through which to explore forms of protection against displacement that might involve local architects, contractors, engineers, and residents alike.

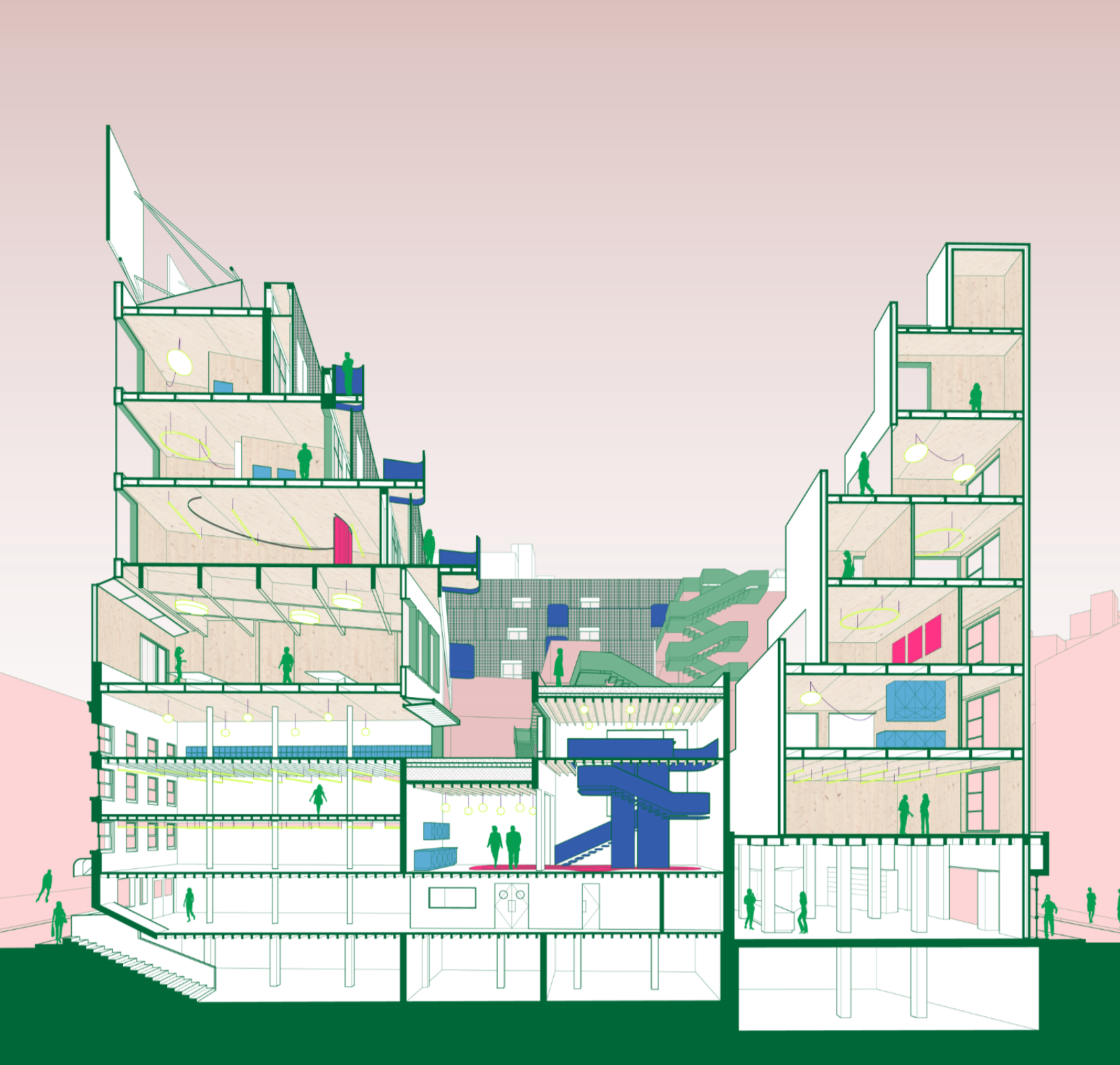

By maximizing the block’s Floor Area Ratio (FAR), the community of workers, retirees, experts, and visitors inhabiting the block can expand their space through an “overbuild.” The existing structures range in height and age: one historic building from 1790 sits among others constructed between 1900 and 1920 using brick masonry, along with a few reinforced concrete structures built in the 1970s. But, before any overbuild begins, wood partitions, floors, and structural replacements are incrementally introduced, replacing aging building components within existing rooms and homes, extending the life of the block, improving its energy efficiency, and potentially extending the life of residents (wood is shown to improve indoor air quality and lower blood pressure). Community services are established within the vacant ground-floor retail, alleyways, and rooftops, where planning and protocols for care are discussed and designed from the inside out. Materials flow through the block and are refurbished, reinstated, or resold. Life becomes more circular. Eventually, three new terraced levels bridge across the existing buildings, and encircle the new courtyard at the center of the block. The additional housing is clad in a south-facing system of Trombe wall gardens, which use thermal mass to heat the building in the winter, stabilizing interior temperature and reducing energy loads, but also producing food and oxygen for the block. The shallow greenhouses provide time and space for gardening and learning about food, while north and east facing facades bring in a shared income through a series of billboards. The block becomes more resilient: circular structures of environmental and social resilience enable residents to engage in long-term community-driven planning, confident in their protection from displacement.

Nine Reciprocities is not a solution; rather, it is a means of exploring a new, more circumspect role for architecture and architects, which reiterates the profession’s commitment to craft and careful consideration of space, while adding a new dimension of material stewardship — all in service of an existing community’s needs and directions.

The architect is just one actor in the physical and social lifecycles of buildings, where “design” is never a one-way directive. Architects are meant to listen, and to build buildings that are good listeners too. How can architectural practice help keep communities intact in the face of climate change and rising inequality? Nine Reciprocities is a 100-year vision for a self-sustaining block in New York City. Through vertical adaptive reuse of existing buildings, we imagine a series of spatial, material, financial, and social platforms for expanding existing communal life. We looked at nine different ways that architecture can serve existing forms of mutual aid and collectivity over this time span: Assembly, Daycare, Gym, Workshop, Store, Office, Greenhouse, Bank, and the Skin.

Our speculations are focused on Manhattan’s Community District Three (CD-3), an area that includes the Lower East Side, Two Bridges, and Chinatown. Each of these neighborhoods faces distinct socio-economic and socio-political challenges; the threat of displacement and exclusion looms equally over all of them. Worrying signs that CD-3 may be transitioning to an exclusionary neighborhood, where low-income tenants are unable to afford rent, are already becoming visible: One Manhattan Square tower demolished a Pathmark grocery store frequented by the middle-income residents of Two Bridges, in addition to obstructing views of the East River and Brooklyn waterfront. Despite ongoing opposition to One Manhattan Square, four more towers are still planned within the same block, while neighborhood groups such as The Coalition to Protect Chinatown and the Lower East Side organize actions against landlords and developers. Analysis from the Urban Displacement Project suggests CD-3 is one of the last areas of Manhattan to fully gentrify. Their data show that large parts of the district are at risk of, or undergoing, gentrification, while remaining areas are deemed “exclusionary” for low-income residents. For these reasons, we thought a representative block in CD-3 would be a useful site through which to explore forms of protection against displacement that might involve local architects, contractors, engineers, and residents alike.

By maximizing the block’s Floor Area Ratio (FAR), the community of workers, retirees, experts, and visitors inhabiting the block can expand their space through an “overbuild.” The existing structures range in height and age: one historic building from 1790 sits among others constructed between 1900 and 1920 using brick masonry, along with a few reinforced concrete structures built in the 1970s. But, before any overbuild begins, wood partitions, floors, and structural replacements are incrementally introduced, replacing aging building components within existing rooms and homes, extending the life of the block, improving its energy efficiency, and potentially extending the life of residents (wood is shown to improve indoor air quality and lower blood pressure). Community services are established within the vacant ground-floor retail, alleyways, and rooftops, where planning and protocols for care are discussed and designed from the inside out. Materials flow through the block and are refurbished, reinstated, or resold. Life becomes more circular. Eventually, three new terraced levels bridge across the existing buildings, and encircle the new courtyard at the center of the block. The additional housing is clad in a south-facing system of Trombe wall gardens, which use thermal mass to heat the building in the winter, stabilizing interior temperature and reducing energy loads, but also producing food and oxygen for the block. The shallow greenhouses provide time and space for gardening and learning about food, while north and east facing facades bring in a shared income through a series of billboards. The block becomes more resilient: circular structures of environmental and social resilience enable residents to engage in long-term community-driven planning, confident in their protection from displacement.

Nine Reciprocities is not a solution; rather, it is a means of exploring a new, more circumspect role for architecture and architects, which reiterates the profession’s commitment to craft and careful consideration of space, while adding a new dimension of material stewardship — all in service of an existing community’s needs and directions.

A response to Urban Design Forum’s Call for Ideas: City Life After Coronavirus

Location: New York, NY

A collaboration with Drawing Agency

See the project on Future Architecture.