Three Material Stories

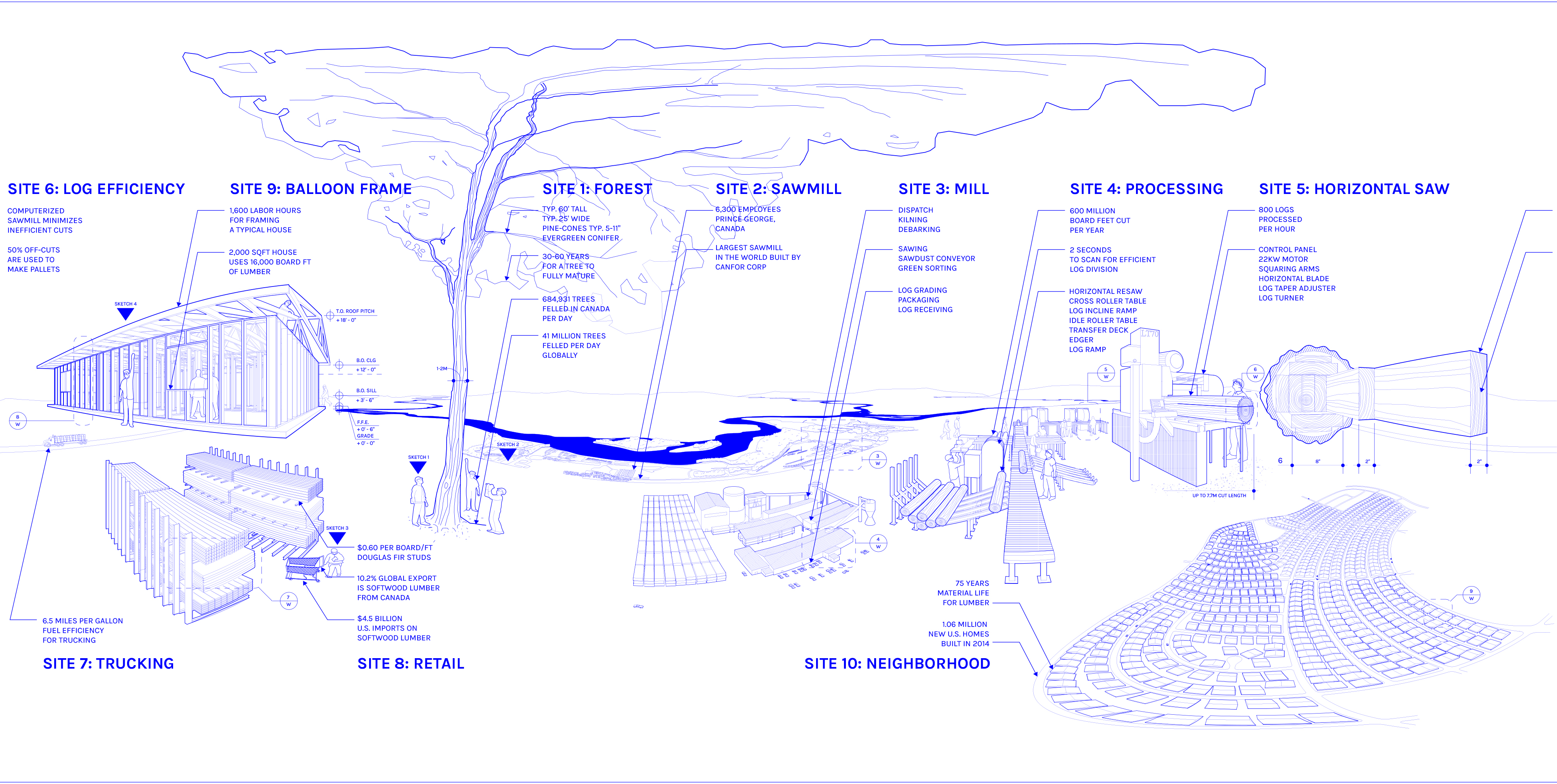

Drawing something that cannot be seen has a long history. The invisible aspects of architecture—the seemingly “insubstantial,” in a material sense—are as consequential, however, as architecture’s more easily drawn, formal attributes. That which is invisible and visible—webs of events, variations of form, secrets, surveillance, labor, legislation, energy, waste, use, desire, agency, friction, consumption and production, the texture of wood or the heat of molten steel—should all be drawn in relation to each other. The embodied energy drawings for this book explore multiple scales and take the form of a set of “material stories” and a set of “site sketches.” The material stories explore three common architectural components: steel, concrete, and wood. Each story involves a narrative arc from extraction to factory production to transportation to construction as a building. The site sketches zoom in to specific locations in the material stories and interrogate the processes and interconnections involved, often speculating about alternatives. These sketches use architectural notation not to narrow in on precise specifications but to open up new directions for design. In order to be addressed in a meaningful and scalable way in architecture, embodied energy needs to be designed. And in order to be designed, it needs to be drawn.

These drawings of the invisible forces of architectural materials take the form of Plate Carrée projections. The pages that follow become spaces where the story of embodied energy is unrolled and made accessible to the designer through a kind of “metric vision,” immersively positioning the body inside or out, above or below a series of events of changes in material state. Though its origins are debated, Plate Carrée projection also has a long history. From the Greco-Roman maps of Eratosthenes, Marinus of Tyre, and Claudius Ptolemy to “Air Age” cartography during World War II, Plate Carrée now exists in the twenty-first century as the universal standard for geographic information systems (GIS). As one of the simplest forms of projection, Plate Carrée—French for “flat square”—is the cylindrical unrolling of a sphere. In the case of global mapping, the latitudinal and longitudinal lines are transformed into an equidistant grid where the north and south poles are expanded from a single point into a line. Every kind of projection has inherent distortion, and Plate Carrée is the culprit of our distorted geographical consciousness, with distances comparatively precise at the equator and increasingly exaggerated to the north and south. However, by organizing the spatial information of a sphere into measurable coordinates, the Earth’s surface can be manipulated on a single piece of paper.

What began as one of the first calculations of the curvature of our planet evolved into a tool for air warfare and then quietly slipped in as the backbone for all raster-imaging data sets. Plate Carrée is still evolving as a representational tool, away from the curved surface of the globe toward the curved surface of the eye. Rather than projecting forward, unrolling the outside surface of a sphere, space can be projected from the inside, as if we are inhabiting the sphere. The human field of view extends 180° from the left to the right and 150° up and down, but we constantly sense the other 180° by 210° of our environment. [FIG. 2] Because we only see so much, maneuvering through the world requires eyesight to work in tandem with memory. For our visual scope to be useful, we must assume a certain truth about the space out of view, or hidden behind us, based on past events. We stitch together multiple perspectives in time to create a comprehensive image of the present.

This act of filling in unseen spaces is at play in the projection drawings of the Earth, but it also remains indispensable in the field of architecture. Perspective projection organizes visible forms along invisible lines of sight in order to describe depth; parallel projection uses three axes in order to describe the visible and invisible parts of measurable forms. Plate Carrée projection achieves both. Imagine an observer ensconced in a sphere, her or his eyes at the center. Equidistant rays are shot from the center of the sphere in all directions until intercepted by mass. The length of each ray is measured and projected back onto the sphere, tracing the details, scale, and depth of a physical space in relation to the viewer’s position. Unrolling the sphere into a grid, we find that each square maintains the relationships between forms, describing what is visible (in front of the observer) and invisible (behind the observer) on a single piece of paper. When a square coordinate grid and all four cardinal perspectives unite on the page, the rules for drawing space dramatically change. Straight lines become circles; curved lines become straight. The warping forms insinuate a new representational language.

Immersive representation has the potential to transport the observer. When this image is rolled back up into a sphere and viewed from within, the body of the observer and the body of the designer become linked—as if they are looking through each other’s eyes. When the human field of view is activated inside of a Plate Carrée drawing, first-person observation becomes part of the design process. Physically turning left, right, up, and down allows parts of the drawing to pass in and out of view and scale to become relative to the viewable area. When many drawings come together to form a space, transformation becomes linked to bodily movement and spatial sequence is no longer linear but associative, collapsing a story into an empathic experience.

In 1972 the Blue Marble project, the first effort to obtain color images of the planet from space, transported the viewer off the ground and into Apollo 17, where the image of the Earth was captured on film sensitive to the natural light reflecting off the surface of clouds, land, and sea. Wrapped in a fog, parts of the Earth were visually impenetrable, unmappable, and thus uncontrollable. To better analyze the impact of invisible forces, mapping space and time on the planet’s surface, more than thirty years later NASA’s Blue Marble: Next Generation captured Earth in pixels, bits of information rather than light, and reassembled it in a fictional, perhaps more palp

able, state, removing any occlusions. Visualizing more of the unseen shows the impact we have on our visible world in higher resolution. It was a military analyst in 1832 who first wrote about fog—the fog of war—as an uncertainty that takes many shapes, hindering the perceivability of the whole. As designers of the environment, we cannot allow events that occur behind us, out of view, or behind closed doors to go unnoticed and remain outside of our scope. In short, when the fog rolls in, progress is prevented. And without discernment and sight, foresight and hindsight, fog is positioned once again to engulf the globe.

These drawings of the invisible forces of architectural materials take the form of Plate Carrée projections. The pages that follow become spaces where the story of embodied energy is unrolled and made accessible to the designer through a kind of “metric vision,” immersively positioning the body inside or out, above or below a series of events of changes in material state. Though its origins are debated, Plate Carrée projection also has a long history. From the Greco-Roman maps of Eratosthenes, Marinus of Tyre, and Claudius Ptolemy to “Air Age” cartography during World War II, Plate Carrée now exists in the twenty-first century as the universal standard for geographic information systems (GIS). As one of the simplest forms of projection, Plate Carrée—French for “flat square”—is the cylindrical unrolling of a sphere. In the case of global mapping, the latitudinal and longitudinal lines are transformed into an equidistant grid where the north and south poles are expanded from a single point into a line. Every kind of projection has inherent distortion, and Plate Carrée is the culprit of our distorted geographical consciousness, with distances comparatively precise at the equator and increasingly exaggerated to the north and south. However, by organizing the spatial information of a sphere into measurable coordinates, the Earth’s surface can be manipulated on a single piece of paper.

What began as one of the first calculations of the curvature of our planet evolved into a tool for air warfare and then quietly slipped in as the backbone for all raster-imaging data sets. Plate Carrée is still evolving as a representational tool, away from the curved surface of the globe toward the curved surface of the eye. Rather than projecting forward, unrolling the outside surface of a sphere, space can be projected from the inside, as if we are inhabiting the sphere. The human field of view extends 180° from the left to the right and 150° up and down, but we constantly sense the other 180° by 210° of our environment. [FIG. 2] Because we only see so much, maneuvering through the world requires eyesight to work in tandem with memory. For our visual scope to be useful, we must assume a certain truth about the space out of view, or hidden behind us, based on past events. We stitch together multiple perspectives in time to create a comprehensive image of the present.

This act of filling in unseen spaces is at play in the projection drawings of the Earth, but it also remains indispensable in the field of architecture. Perspective projection organizes visible forms along invisible lines of sight in order to describe depth; parallel projection uses three axes in order to describe the visible and invisible parts of measurable forms. Plate Carrée projection achieves both. Imagine an observer ensconced in a sphere, her or his eyes at the center. Equidistant rays are shot from the center of the sphere in all directions until intercepted by mass. The length of each ray is measured and projected back onto the sphere, tracing the details, scale, and depth of a physical space in relation to the viewer’s position. Unrolling the sphere into a grid, we find that each square maintains the relationships between forms, describing what is visible (in front of the observer) and invisible (behind the observer) on a single piece of paper. When a square coordinate grid and all four cardinal perspectives unite on the page, the rules for drawing space dramatically change. Straight lines become circles; curved lines become straight. The warping forms insinuate a new representational language.

Immersive representation has the potential to transport the observer. When this image is rolled back up into a sphere and viewed from within, the body of the observer and the body of the designer become linked—as if they are looking through each other’s eyes. When the human field of view is activated inside of a Plate Carrée drawing, first-person observation becomes part of the design process. Physically turning left, right, up, and down allows parts of the drawing to pass in and out of view and scale to become relative to the viewable area. When many drawings come together to form a space, transformation becomes linked to bodily movement and spatial sequence is no longer linear but associative, collapsing a story into an empathic experience.

In 1972 the Blue Marble project, the first effort to obtain color images of the planet from space, transported the viewer off the ground and into Apollo 17, where the image of the Earth was captured on film sensitive to the natural light reflecting off the surface of clouds, land, and sea. Wrapped in a fog, parts of the Earth were visually impenetrable, unmappable, and thus uncontrollable. To better analyze the impact of invisible forces, mapping space and time on the planet’s surface, more than thirty years later NASA’s Blue Marble: Next Generation captured Earth in pixels, bits of information rather than light, and reassembled it in a fictional, perhaps more palp

able, state, removing any occlusions. Visualizing more of the unseen shows the impact we have on our visible world in higher resolution. It was a military analyst in 1832 who first wrote about fog—the fog of war—as an uncertainty that takes many shapes, hindering the perceivability of the whole. As designers of the environment, we cannot allow events that occur behind us, out of view, or behind closed doors to go unnoticed and remain outside of our scope. In short, when the fog rolls in, progress is prevented. And without discernment and sight, foresight and hindsight, fog is positioned once again to engulf the globe.

Completed in 2017

Exhibited at XXII Triennale di Milano, Broken Nature: Design Takes on Human Survival

A series of hand drawings, the cover art, and a critical essay on projection commissioned for Embodied Energy and Design: Making Architecture Between Metrics and Narrative, edited by David Benjamin, and published by Lars Muller and Columbia Books.

Read the essay